Turning Up the Heat: Using Heat Training to Boost Fitness (Even If You’re Not Racing in the Heat)

- Pete Wilby

- Dec 22, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 24, 2025

When most athletes hear the phrase heat training, they think acclimation - surviving a hot race or preparing for a foreign climate. But what if heat wasn’t only a tool for coping? What if it were a tool for improving?

Recently, after being prompted by a coached athlete earlier in 2025, I’ve been investigating bike-based heat-training protocols not just for acclimation but also as a deliberate way to elevate fitness during everyday training. And the more I see, the more convinced I am.

My Hypothesis

I hoped to observe an improved functional threshold in swimming, cycling, and running following a five-week heat-training protocol on the indoor bike trainer.

A Look at The Research

Whilst heat training isn't exactly mainstream among age-groupers looking for ways to train better, it's far more common among pros.

The sauna is a widely used resource by pro athletes, generally associated with relaxing of course, by most. Simply sitting in a sauna before training constitutes 'passive heat training' and has been shown to substantially increase plasma volume in well-trained athletes (1).

Increasing blood plasma volume enhances athletic endurance by increasing cardiac output (the amount of blood the heart pumps each beat). The increase in blood plasma volume improves oxygen and nutrient delivery, facilitating waste removal, and aiding body temperature regulation through increased blood flow to the skin, all of which delay fatigue and improve performance.

Prof Mike Tipton and colleagues found that a five-week heat-training protocol increased haemoglobin mass in elite cyclists (2). Many high-performance coaches worldwide utilise both passive and active heat training (3). It looks like heat can be used just like altitude - a controlled stressor layered gently into your programme to stimulate adaptation and give you a performance lift, even if your goal race is in perfectly mild British drizzle.

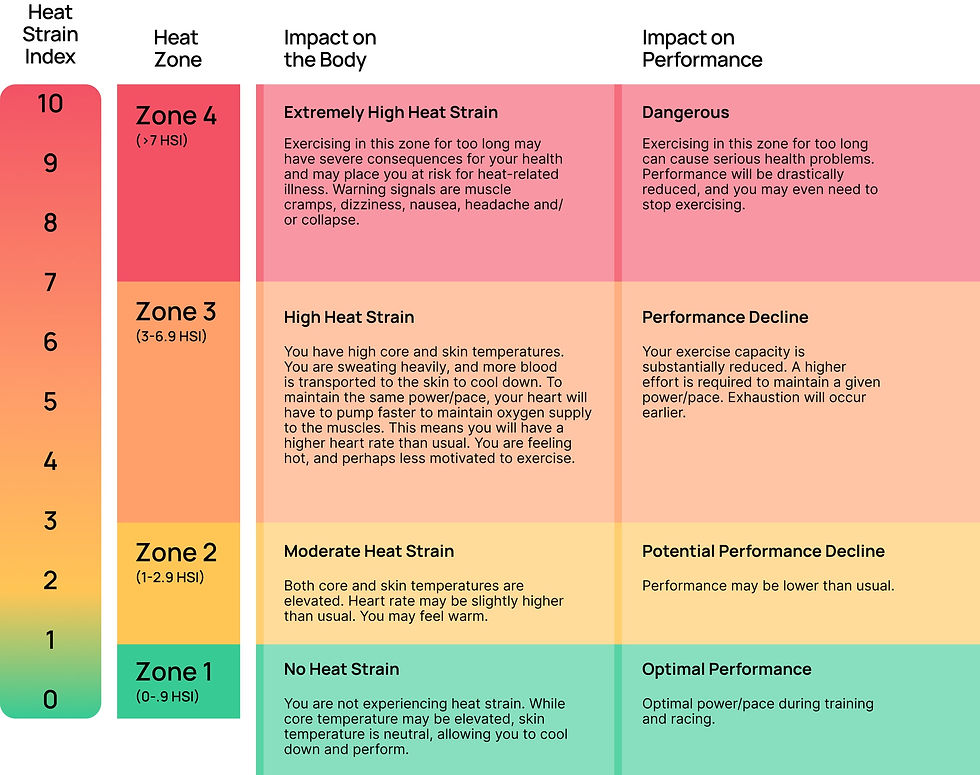

Research suggests that, as with regular training - you train, and the body responds by fixing-up stronger in case you train again - heat training prepares the body to cope better in heat (4). A heat stress index was first developed by Robert G. Steadman in 1979 to categorise atmospheric heat and its effects on the body, but not exercise-specific zones. More recently, a company called CORE developed heat index scoring for athletes (5).

The heat stress index has been created for athletes to use, much like training zones or RPE, except for heat. This is crucial when using active heat training to ensure that athletes become sufficiently hot to elicit training gains, but not so hot that the heat becomes dangerous or ineffective.

To keep things simple, based on a protocol from the CORE website, I developed a bike heat-training protocol, tuned for some athletes I coach, and I had to try it myself as well. I didn't want to go as far as lab conditions, but I did want to test the benefit of an indoor bike heat protocol on running and swimming, as well as indoor bike performance.

Firstly, Some Results

W1 | < Five-week heat training protocol > | W7 | ||||

FTP | CSS | Run FTP | FTP | CSS | Run FTP | |

229w | N/A | N/A | 256w | 1:33/100m | N/A | |

193w | 01:36/100m | 3:51/km | 224w | 1:30/100m | 3:45/km | |

233w | 01:49/100m | N/A | 246w | 1:45/100m | N/A | |

267w | (used a slightly different re-test) | 229w | ||||

187w | 1:51/100m | N/A | 194w | 1:52/100m | N/A |

Interpreting the Results

As you can see, the gains were significant - much bigger than I initially expected. All but one athlete improved cycling FTP. Two of the three participants who tested swim CSS showed significant improvement. All athletes reported feeling fitter. All but one athlete found it very hard to motivate themselves. Interestingly, from a personal perspective, I didn't see the December sea swimming (for coaching purposes) any harder to acclimate to; if anything, I honestly feel that was made easier. I obtained usable data from only one athlete on run FTP (as field testing is not always a fair comparison), who improved considerably from an already high benchmark.

The protocol was performed in the off-season, following a two- to four-week recovery block from racing for all athletes except one, me, who hadn't been training much and expected to improve with any form of training. Some athletes were already competing at a high level and extremely fit before starting, yet they still showed substantial improvements.

However - and this is important - it was TOUGH. The intensity isn’t in the power produced, because that stays low; it’s in the fact that you are effectively doing the heat intensity of an FTP test every day, just with reduced output. That accumulated internal stress is where the magic (and the challenge) really lies. But that is really tough.

Method - How the Protocol Works

The very first session was a sweat test, used to determine how salty a sweater you are and therefore how much sodium you’re likely to need. In week one, you should also complete baseline testing - FTP, CSS, run FTP, and any additional metrics you want to track for comparison.

Before and after every session, you must weigh yourself naked to calculate exactly how much fluid you lose (or occasionally possibly gain) through sweat. Using the sweat-rate calculator. You then determine the precise amount of rehydration required. This part is essential - if you get the hydration wrong, the adaptation won’t happen. The protocol depends on proper rehydration, rather than dehydration.

A primary concern was the additional risk that heat training could pose. We made sure to be informed primarily by the heat strain index and, secondly, by the heart rate response. For example, athletes need to feel in a heat zone of three to elicit the effects, whereas four is too high. Additionally, when HR exceeds FTP, it is a good indication that this intensity may not be sustainable; likewise, the absence of HR drift under heat stress indicates that heat is unlikely to have an effect (that said, if you are already well adapted to the heat, it may not mean anything). During the process, I learned to adjust the protocol to achieve optimal outcomes. Some athletes had to add layers, while others had to adjust their power.

Across weeks 2–6, each session included a progressively increasing “heat exposure” portion. To maintain a consistent heat load, we all wore a sauna suit (hoods up) whilst completing the turbo session, which reliably raised core temperature, even at low wattage.

Finally, week 7 is another full testing week - FTP, CSS, and run FTP again - allowing you to compare back to baseline and quantify the effect of the block.

Key Principles of Heat Training

Stay aerobic. Power output remains low (the top of Z2 is a good guide), but internal load rises. If you start drifting into Z4 HR, dial the power down.

Hydrate properly. Determine your sodium needs per litre. Drink to thirst. Weigh yourself before and after the session, and replace 1.5× the fluid lost. SWEAT RATE CALCULATOR.

One focused block, then maintenance. Treat heat training like a training camp stimulus. We used a five-week block and plan to schedule roughly biweekly maintenance sessions afterwards.

Use the heat index score. Most adaptation appears in heat zone three. Zone four becomes risky and is not recommended.

What You’ll Notice

Athletes reported:

A stronger aerobic engine across all three disciplines

Lower HR drift in steady sessions

A fresher feel at race pace

Improved threshold markers

Better durability in longer sessions

A surprising “second gear” across all disciplines, after the block concludes

Lowered motivation to do more heat

When to Use It

I think winter is ideal: minimal outdoor hours, plenty of controlled indoor riding. I would allow seven weeks—one testing week, five progressive heat weeks, and a final testing week.

Conclusion - Final Thoughts

Just like drills in the pool or technical work on the run, heat training is a targeted tool. It’s not glamorous, but it works. Layered gently into your training, it can quietly shift your physiology in a way that pays off.

If you’re curious about trying a structured heat block or need help designing one around your current plan, drop me a message.

You can book a coaching consultation.

You can follow my free heat training protocol.

You can book in-depth fitness testing (Book two tests for the heat protocol - we will guide you throughout).

Happy TriathlOn-ing,

Pete

References:

Comments